综述|眼动追踪技术在神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍中的研究进展

时间:2025-01-17 12:10:23 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

摘 要 眼动追踪技术是记录眼球运动及注视位置随时间及任务变化的检查方法,常见眼动参数包括扫视、平滑追求、注视、视觉搜索等。神经退行性疾病,如阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer disease,AD)、额颞叶痴呆(fronto temporal dementia,FTD)、路易体痴呆(dementia with Lewy bodies,DLB)、帕金森病(Parkinson disease,PD)、多系统萎缩(multiple system atrophy,MSA)、进行性核上性麻痹(progressive supranuclear palsy, PSP)、运动神经元病(motor neuron disease,MND)和皮质基底节变性(corticobasal degeneration,CBD)等所致的认知功能障碍,在上述眼动参数中存在不同程度及不同表现的异常。如不同程度的扫视潜伏期延长、扫视错误率增加等。眼球运动追踪技术在早期识别、诊断及辅助鉴别诊断各类神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍方面具有重要价值,是一种无创便捷、客观准确的新方法。

关键词

眼动追踪技术;认知功能障碍;痴呆;阿尔茨海默病;神经退行性疾病

神经系统退行性疾病是引起老年人认知功能障碍的主要原因之一。目前全球约有5000万痴呆症患者,到2050年,患病人数将达到1.52亿人[1]。目前认知功能障碍筛查手段主要依赖于量表评估,但其易受文化程度及患者状态等主观因素影响。而具有更高诊断价值的脑脊液检查及分子影像检查因费用昂贵、有创、技术复杂等原因,难以用于人群筛查。近年来有研究[2-3]发现,眼动追踪技术作为一种非侵入性的方法,可用于识别和评估认知功能并监测其进展和严重程度,揭示认知加工过程以及认知缺陷。因此,本文就眼动追踪技术在常见的引起认知功能障碍的神经退行性疾病中的研究进行综述,了解不同疾病的眼动特征,以期为神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍的早期识别、不同类型认知障碍性疾病的辅助鉴别诊断提供新的思路和方法。

1 眼动追踪技术概述

眼动追踪技术是记录眼球运动及注视位置随时间及任务变化的检查方法。目标物体的图像要想投射并维持在视网膜的中央凹上,需要各种眼球运动配合实现[4]。常见眼动任务包括扫视、平滑追踪、注视、视觉搜索等。

1.1 扫视 扫视的目的是将注视从一个目标快速转移到另一个目标。扫视运动分为反射性扫视(自发性扫视、扫描性扫视)和复杂性扫视(反扫视、预测扫视、记忆扫视)。我们通常采用峰速度、准确度和潜伏期来评价患者的扫视表现。

1.2 平滑追踪 平滑追踪是指受试者持续跟踪并注视移动的目标物。研究常用速度增益(眼球移动速度和目标移动速度之比)、追踪持续时间以及追踪中断的次数等指标来评估平滑追踪的稳定性。追踪过程中还会出现“追赶”“预备”和“预期”等扫视[5]。

1.3 注视 注视是指眼睛在目标物上维持,时长通常在200~300 ms。注视是随着微扫视、眼球漂移和震颤的组合而持续移动的过程。在没有视觉干扰的情况下,眼球偏离固定目标的运动,被称为扫视入侵。方波急跳( square wave jerks,SWJ)是注视过程中最常见的入侵类型。

1.4 视觉搜索 视觉搜索是指以眼球运动在视觉环境中查找感兴趣的对象或目标,它利用自上而下的认知,来组织和整合视觉所涉及的认知处理和控制眼球运动的动眼神经[6]。我们常常会采用瞳孔大小、扫描区域、注视时间、注视次数等相关眼动指标来评估视觉搜索表现。

2 眼动追踪技术在神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍中的研究

2.1 阿尔茨海默病(AD) AD患者常会经历主观认知下降(subjective cognitive impairment,SCI)、轻度认知障碍( mild cognitive impairment,MCI)和AD痴呆(ADD)三个阶段。已有研究[7]开始利用眼动追踪技术对AD认知功能下降进行检测。

研究[8] 认为在MCI中视觉功能缺陷比记忆障碍出现得早,并且这些缺陷可以反映在眼球运动模式上。MCI患者常表现为扫视潜伏期延长、扫视错误率高,并且错误扫视次数与神经心理评分存在负相关[9]。眼动技术可用于区分遗忘型(amnestic MCI,aMCI)和非遗忘型MCI(non-amnestic MCI,naMCI)。部分研究发现aMCI反扫视潜伏期较naMCI组延长及未校正的扫视错误比例较naMCI组增高[10-11],并且aMCI患者在扫视过程中会出现比naMCI更多的“快速”扫视[12-13]。增加的扫视错误率及较高的未纠正错误比例被视为早期检测aMCI的特异性指标[14]。最新研究[15] 表明aMCI患者的视觉搜索行为也存在异常表现。未来如果将眼动追踪技术与人口统计学和认知测试分数相结合,可增强对aMCI的预测,使其成为一种无创的、客观有效的识别认知功能障碍早期阶段的方法[16-17]。

在AD患者与MCI患者中,AD患者的反扫视潜伏期明显增长,错误率明显增高[11-19]。NOIRET等[20]研究也表明AD患者的扫视错误率(19%)显著高于与aMCI(12%)和健康对照组(4%)。最新一项研究表明正确扫视率能够以87%的敏感性和86%的特异性区分AD和健康对照组,而未纠正错误率以84%的敏感性和83%的特异性区分两者[10]。反扫视错误率增加以及较高的未纠正扫视错误率是AD的特征眼动表现。但目前AD患者反扫视性能差的机制仍不清楚,有研究认为反扫视过程中的抑制信号起源于背外侧前额叶皮质(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,DLPFC),可能与DLPFC的退变导致抑制性功能障碍相关[21]。但其他研究认为DLPFC的退变导致AD患者工作记忆受损,因而导致反扫视的错误扫视[22],这两种机制的变化都可能导致患者的反扫视性能降低。

平滑追踪任务中,有研究[23]发现AD患者追踪启动时的潜伏期增加、初始加速度和增益降低,追踪过程中AD患者还会频繁地进行扫视,例如预期扫视以及代偿性扫视等。并且随着认知功能的下降,代偿性扫视会发生得更频繁[24]。

在注视的研究中,AD患者的注视时间明显缩短,扫视入侵频率增加,会出现较多的方波急跳[25]。BYLSMA等[26] 在对AD患者行18个月的注视及扫视检测随访中发现AD患者侵入性扫视次数的渐进式增加,并且这种增加与痴呆严重程度的增加相关,而扫视潜伏期则无明显变化。这说明评估AD的进展变化,注视相关指标比扫视指标更为敏感。

有研究开始探索AD患者在结合记忆的眼动任务、视觉搜索、场景探索等的眼动表现。ERASLAN 等[15]对AD患者进行了真实图像的视觉搜索,发现患者注视时间变短、扫描图像频率及视觉扫描面积均减少,表明AD患者在处理视觉信息和适应环境能力有所下降。而他的另一项前瞻性研究发现[27]与aMCI和健康对照者相比,AD患者在干扰物上的注视次数及注视时间均长于目标物,这表明AD患者的视觉搜索更专注于干扰物。一些研究[28-29]还发现AD患者的瞳孔大小变化与认知水平相关,随着任务执行所需的认知负荷增加,瞳孔直径会越来越大。

2.2 路易体痴呆 路易体痴呆(dementia with Lewy bodies,DLB)主要表现为波动性认知障碍、视幻觉和类似帕金森病的运动症状,目前对其眼球运动研究十分有限。MOSIMANN等[30]发现DLB患者的扫视潜伏期长于痴呆的PD和AD患者。纠正错误扫视的次数也少于AD患者。在此基础上,KAPOULA等[31]还发现DLB患者扫视的准确度和峰值速度都降低。这些研究表明了眼球运动可能具有对这些退行性疾病进行鉴别诊断的潜力。但以上研究由于其样本量较少且以扫视运动为主,需要扩大样本量,并涉及眼球运动的其他形式进行研究,以求探索DLB的特异性眼动指标。

2.3 额颞叶痴呆 额颞叶痴呆(fronto temporal dementia,FTD)可分为行为变异型(behavioral variant FTD,bvFTD)、进行性非流利性失语症(progressive nonfluent aphasia,PNFA)和语义痴呆(semantic dementia,SD)[32]。额颞叶负责控制眼球运动的区域之间存在广泛的重叠,因此有研究开始探索FTD患者的眼球运动。GARBUTT等[33]发现bvFTD和SD患者的扫视潜伏期、扫视速度、平均注视时间都无显著异常。但bvFTD患者的错误扫视次数却明显高于SD患者。FTD患者的眼球运动异常取决于受疾病影响的大脑区域,SD患者可能因其顶叶和额叶都保留而无明显异常眼动表现。在注视任务中,bvFTD患者的SWJ次数增多,注视时间缩短,但在平滑追踪上表现却没有明显异常[34]。平滑追踪是否具有异常仍有不同观点,其他研究[35]认为FTD患者的平滑追踪是有受损的。在DERAVET等[36]研究中,一名携带C9ORF72突变的无症状参与者表现出了与FTD患者相似的眼动行为模式。在测量后的3年内,该参与者出现了FTD症状,这似乎表明FTD患者可能在临床症状出现前就有眼球运动缺陷,眼球运动或许可以成为预测及辅助疾病诊断的工具。

2.4 帕金森病 帕金森病(Parkinson disease,PD)患者的认知能力分为正常(Parkinson disease-normal cognition,PD-NC)、轻度认知障碍(Parkinson disease-mild cognitive impairment,PD-MCI)到帕金森痴呆(PDD)[37]。PDD患者的反射性扫视和复杂扫视表现的损害大于单纯皮质痴呆(如AD)或PD-NC患者[30]。认知功能越严重的患者其反扫视运动异常越明显[38]。MOSIMANN 等[30]研究发现PDD患者扫视潜伏期明显长于PD患者,并且在复杂扫视中PDD患者纠正错误扫视的次数也多于PD患者。随着认知功能障碍的严重程度,反扫视错误率逐渐增加[39-40]。对PD患者进行视觉探索,发现所有PD患者的注视时间都延长,但认知障碍的PD患者的注视时间最长(PDD患者的注视时间比PD-NC患者长40 ms)[41]。并非每个PD患者都会有平滑追踪异常。有研究[42]显示新发的PD患者也可表现出速度增益降低。但其他研究[43]认为,PD患者平滑追踪表现并无显著异常。

目前反扫视被认为是评估PD患者认知水平最有效的眼球运动,其中扫视潜伏期延长和扫视错误率高或许可作为我们评估认知功能的眼动参数。但根据目前的证据,它们缺乏足够的敏感性和特异性来作为独立的诊断工具[44]。

2.5 多系统萎缩 MSA中受影响的几个脑区,如大脑皮层、纹状体、中脑和小脑,都与视觉功能密切相关。在扫视过程中,MSA的峰值速度均降低,但以小脑症状为主的多系统萎缩(MSA-Cerebellar,MSA-C)的加速和减速持续时间无明显异常[45],以帕金森为主的多系统萎缩(MSA-Parkinsonian,MSA-P)的加速和减速持续时间却是延长的[46]。BROOKS等[47]研究发现MSA 患者(未指定亚型)的扫视潜伏期长于PD患者,并且扫视错误率也高于PD患者,增加的扫视错误率和更长的扫视潜伏期或许可能成为区分 PD 和 MSA 的有用标志物。平滑追踪中,PINKHARDT等[48]的研究还发现MSA患者的增益下降比PD患者更为明显,MSA-C 患者的追踪增益低于MSA-P[49]。

2.6 进行性核上性麻痹 进行性核上性麻痹(progressive supranuclear palsy,PSP)患者的眼球运动都有异常,常表现为低视和缓慢的扫视速度和凝视受限。在早期PSP患者仅表现为缓慢的垂直扫视,随着疾病进展,水平扫视也会受到影响[50]。PSP的眼动异常也有可能不存在或在病程晚期才出现。因此有研究期待其他眼动指标来判断PSP。PSP患者在进行各种扫视时的准确性都较低[51],TERAO等[52]研究还发现PSP的扫视峰值速度降低、持续时间延长,其中进行性核上性麻痹-小脑共济失调型(progressive supranuclear palsy-cerebellar ataxia,PSP-C)患者的变化最明显,其次是进行性核上性麻痹-理查森综合征(progressive supranuclear palsy-Richardson syndrome, PSP-RS)患者,而进行性核上性麻痹-帕金森综合征型(progressive supranuclear palsy-Parkinsonism,PSP-P)患者变化较小,进行性核上性麻痹-进展性冻结步态型(progressive supranuclear palsy-progressive gait freezing, PSP-PGF)患者正常。CHOI等[53]研究也认为PSP-RS相较于PSP-PGF、PSP-P的眼球运动异常更明显。但PINKHARDT等[54]却认为两组PSP患者(PSP-RS、PSP-P)之间的扫视峰值速度和平滑追踪都没有差异。部分研究还发现确诊PSP的患者表现出了更大、更频繁的SWJR[55]。

2.7 运动神经元病 一项对两名尸检证实的运动神经元病(motor neuron disease,MND)的典型类型肌萎缩侧索硬化(amyotrophic laterl selerophin,ALS)患者的研究表明,其主要的眼球运动表现是核上垂直凝视障碍伴缓慢的垂直扫视[56]。POLETTI等[57]发现眼动异常的ALS患者认知功能障碍更常见。晚期的ALS患者表现为扫视速度减慢以及反扫视错误率的增加[58]。MND患者眼动异常主要表现为扫视潜伏期增加和平滑追逐增益降低。最新一项研究表明在53例MND患者中34例(64.2%)患者出现了眼动异常,并且这些异常表现与疾病严重程度相关[59]。眼球运动似乎可以成为MND预测疾病严重程度的指标。

2.8 皮质基底节变性 基底神经节在眼跳的产生中起着关键的作用,因此皮质基底节变性(corticobasal degeneration,CBD会出现一些眼动的异常表现。研究[60]发现CBD典型的眼动特征为扫视潜伏期增加(失用症的同侧)、平滑的追逐运动受损和视觉空间功能障碍,部分还可出现扫视速度降低、垂直凝视麻痹等异常表现。CBD 患者扫视潜伏期延长,并且长于PD患者,可能与额叶眼区功能障碍相关[53]。在平滑追踪中,CBD患者追踪开始时的潜伏期也明显增加,水平面和垂直平面的眼球加速度均降低,但垂直方向更为明显[61]。

3 总结与展望

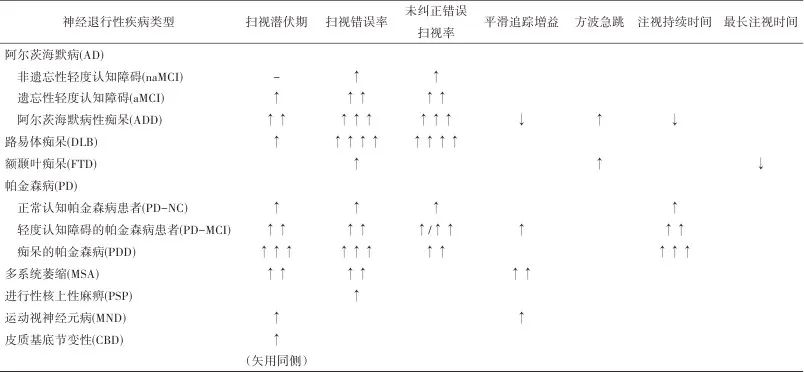

综上,眼球运动追踪技术在神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍的评估、疾病严重程度监测和鉴别诊断方面提供新思路和新方法(表1)。因其具有的无创简便、客观准确、价廉易普及等诸多特点,在社区认知障碍的早期筛查中具有巨大的潜力。未来应结合各疾病生物标志物、功能磁共振等开展更深入的研究,以明确认知加工任务的脑网络机制;并通过多中心、大样本研究,获得大数据,建立基于眼动参数的各疾病认知障碍预测模型,从而指导临床更好地应用此技术进行诊断与鉴别诊断。

表1 各神经退行性疾病认知障碍的眼动参数特征总结Tab.1 Summary of eye movement parameter features of cognitive impairment in neurodegenerative diseases

注:-,与对照组无差异;↑,增加;↑↑,明显增加;↑↑↑,显著增加;↑↑↑↑,大大增加;↓,减少。

参考文献:

1. PATTERSON C, Alzheimer’s Disease International(ADI).World Alzheimer report 2018: The state of the Art of Dementia Research: New Frontiers[R]. UK: London, 2018.

2. BUENO A P A, SATO J R, HORNBERGER M. Eye tracking - The overlooked method to measure cognition in neurodegeneration? [J]. Neuropsychologia, 2019, 133: 107191.

3. RIEK H C, BRIEN D C, COE B C, et al. Cognitive correlates of antisaccade behaviour across multiple neurodegenerative diseases [J]. Brain Commun, 2023, 5(2): fcad049.

4. WALLS G L. The evolutionary history of eye movements[J]. Vision Res, 1962, 2(1-4): 69-80.

5. TOKUSHIGE S I, MATSUDA S, INOMATA-TERADA S, et al. Premature saccades: A detailed physiological analysis[J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2021, 132(1): 63-76.

6. SINGH T, FRIDRIKSSON J, PERRY C M, et al. A novel computational model to probe visual search deficits during motor performance [J]. J Neurophysiol, 2017, 117(1): 79-92.

7. OYAMA A, TAKEDA S, ITO Y, et al. Novel Method for Rapid Assessment of Cognitive Impairment Using High-Performance Eye-Tracking Technology [J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9(1): 12932.

8. SHAIKH A G, ZEE D S. Eye Movement Research in the Twenty-First Century-a Window to the Brain, Mind, and More[J]. Cerebellum, 2018, 17(3): 252-258.

9. OPWONYA J, WANG C, JANG K M, et al. Inhibitory Control of Saccadic Eye Movements and Cognitive Impairment in Mild Cognitive Impairment [J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2022, 14: 871432.

10. ERASLAN BOZ H, KOÇOĞLU K, AKKOYUN M, et al. Uncorrected errors and correct saccades in the antisaccade task distinguish between early-stage Alzheimer’s disease dementia, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging[J]. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn, 2024, 31(3): 457-458.

11. WILCOCKSON T D W, MARDANBEGI D, XIA B, et al. Abnormalities of saccadic eye movements in dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment[J]. Aging, 2019, 11(15): 5389-98.

12. AKKOYUN M, KOÇOĞLU K, ERASLAN BOZ H, et al. Saccadic Eye Movements in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Longitudinal Study[J]. J Motor Behav, 2023, 55(4): 354-372.

13. KOÇOĞLU K, HODGSON T L, ERASLAN BOZ H, et al. Deficits in saccadic eye movements differ between subtypes of patients with mild cognitive impairment[J]. J Clin Exp Neuropsyc, 2021, 43(2): 187-198.

14. ZHANG S, HUANG X, AN R, et al. The application of saccades to assess cognitive impairment among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2023, 35(11): 2307-2321.

15. ERASLAN BOZ H, KOÇOĞLU K, AKKOYUN M, et al. Examination of eye movements during visual scanning of real-world images in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment [J]. Int J Psychophysiol, 2023, 190: 84-93.

16. CHEHREHNEGAR N, NEJATI V, SHATI M, et al. Behavioral and cognitive markers of mild cognitive impairment: diagnostic value of saccadic eye movements and Simon task [J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2019, 31(11): 1591-1600.

17. OPWONYA J, KU B, LEE K H, et al. Eye movement changes as an indicator of mild cognitive impairment[J]. Front Neurosci, 2023, 17: 1171417.

18. YANG Q, WANG T, SU N, et al. Long latency and high variability in accuracy-speed of prosaccades in Alzheimer’s disease at mild to moderate stage[J]. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra, 2011, 1(1): 318-329.

19. OPWONYA J, DOAN D N T, KIM S G, et al. Saccadic Eye Movement in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [J]. Neuropsychol Rev, 2022, 32(2): 193-227.

20. NOIRET N, CARVALHO N, LAURENT É, et al. Saccadic Eye Movements and Attentional Control in Alzheimer’s Disease[J]. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 2018, 33(1): 1-13.

21. KAUFMAN L D, PRATT J, LEVINE B, et al. Antisaccades: a probe into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2010, 19(3): 781-793.

22. EVERLING S, JOHNSTON K. Control of the superior colliculus by the lateral prefrontal cortex[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2013, 368(1628): 20130068.

23. SHAKESPEARE T J, KASKI D, YONG K X, et al. Abnormalities of fixation, saccade and pursuit in posterior cortical atrophy [J]. Brain, 2015, 138(7): 1976-1991.

24. LIN J, XU T, YANG X, et al. A detection model of cognitive impairment via the integrated gait and eye movement analysis from a large Chinese community cohort[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2024, 20(2): 1089-1101.

25. NAKAMAGOE K, YAMADA S, KAWAKAMI R, et al. Abnormal Saccadic Intrusions with Alzheimer’s Disease in Darkness [J]. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2019, 16(4): 293-301.

26. BYLSMA F W, RASMUSSON D X, REBOK G W, et al. Changes in visual fixation and saccadic eye movements in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Int J Psychophysiol, 1995, 19(1): 33-40.

27. ERASLAN BOZ H, KOÇOĞLU K, AKKOYUN M, et al. Visual search in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: An eye-tracking study[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2024, 20(2): 759-768.

28. TOKUSHIGE S I, MATSUMOTO H, MATSUDA S I, et al. Early detection of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease using eye tracking[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2023, 15: 1123456.

29. ZOKAEI N, BOARD A G, MANOHAR S G, et al. Modulation of the pupillary response by the content of visual working memory [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019, 116(45): 22802-22810.

30. MOSIMANN U P, MÜRI R M, BURN D J, et al. Saccadic eye movement changes in Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies[J]. Brain, 2005, 128(Pt 6): 1267-1276.

31. KAPOULA Z, YANG Q, VERNET M, et al. Spread deficits in initiation, speed and accuracy of horizontal and vertical automatic saccades in dementia with lewy bodies[J]. Front Neurol, 2010, 1: 138.

32. TIPPETT D C. Classification of primary progressive aphasia: challenges and complexities[J]. F1000Res, 2020, 9: F1000 Faculty Rev-64.

33. GARBUTT S, MATLIN A, HELLMUTH J, et al. Oculomotor function in frontotemporal lobar degeneration, related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Brain, 2008, 131(Pt 5): 1268-1281.

34. RUSSELL L L, GREAVES C V, CONVERY R S, et al. Eye movements in frontotemporal dementia: Abnormalities of fixation, saccades and anti-saccades[J]. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 2021, 7(1): e12218.

35. BOXER A L, GARBUTT S, RANKIN K P, et al. Medial versus lateral frontal lobe contributions to voluntary saccade control as revealed by the study of patients with frontal lobe degeneration [J]. J Neurosci, 2006, 26(23): 6354-6363.

36. DERAVET N, ORBAN DE XIVRY J J, IVANOIU A, et al. Frontotemporal dementia patients exhibit deficits in predictive saccades[J]. J Comput Neurosci, 2021, 49(3): 357-369.

37. 王丽娟, 冯淑君, 聂坤,等. 中国帕金森病轻度认知障碍的诊断和治疗指南(2020版) [J]. 中国神经精神疾病杂志, 2021, 47(1): 1-12.

38. WALDTHALER J, TSITSI P, SVENNINGSSON P. Vertical saccades and antisaccades: complementary markers for motor and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease[J]. NPJ Parkinsons Dis, 2019, 5(1): 11.

39. WALDTHALER J, STOCK L, STUDENT J, et al. Antisaccades in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis[J]. Neuropsychol Rev, 2021, 31(4): 628-642.

40. ANTONIADES C A, DEMEYERE N, KENNARD C, et al. Antisaccades and executive dysfunction in early drug-naive Parkinson’s disease: The discovery study[J]. Mov Disord, 2015, 30(6): 843-847.

41. ARCHIBALD N K, HUTTON S B, CLARKE M P, et al. Visual exploration in Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia[J]. Brain, 2013, 136(3): 739-750.

42. ZHOU M X, WANG Q, LIN Y, et al. Oculomotor impairments in de novo Parkinson’s disease[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2022, 14: 985679.

43. FUKUSHIMA K, ITO N, BARNES G R, et al. Impaired smooth‐pursuit in Parkinson’s disease: normal cue‐information memory, but dysfunction of extra‐retinal mechanisms for pursuit preparation and execution[J]. Physiol Rep, 2015, 3(3): e12361.

44. ANTONIADES C A, SPERING M. Eye movements in Parkinson’s disease: from neurophysiological mechanisms to diagnostic tools[J]. Trends Neurosci, 2024, 47(1): 71-83.

45. TERAO Y, FUKUDA H, TOKUSHIGE S I, et al. Distinguishing spinocerebellar ataxia with pure cerebellar manifestation from multiple system atrophy (MSA-C) through saccade profiles[J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2017, 128(1): 31-43.

46. Terao Y, Tokushige S I, INOMATA-TERADA S, et al. Differentiating early Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy with parkinsonism by saccade velocity profiles [J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2019, 130(12): 2203-2215.

47. BROOKS S H, KLIER E M, RED S D, et al. Slowed Prosaccades and Increased Antisaccade Errors As a Potential Behavioral Biomarker of Multiple System Atrophy[J]. Front Neurol, 2017, 8: 261.

48. PINKHARDT E H, KASSUBEK J, SÜSSMUTH S, et al. Comparison of smooth pursuit eye movement deficits in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Neurol, 2009, 256(9): 1438-1446.

49. ZHOU H, SUN Y, WEI L, et al. Quantitative assessment of oculomotor function by videonystagmography in multiple system atrophy[J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2022, 141: 15-23.

50. KO T, BRENNER A M, MONTEIRO N P, et al. Abnormal eye movements in parkinsonism: a historical view[J]. Arq Neuro-Psiquiat, 2021, 79(5): 457-459.

51. WRIGHT I H, SEKAR A, JENSEN M T, et al. Reflexive and volitional saccadic eye movements and their changes in age and progressive supranuclear palsy[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2022, 443: 120482.

52. TERAO Y, TOKUSHIGE S I, INOMATA-TERADA S, et al. Deciphering the saccade velocity profile of progressive supranuclear palsy: A sign of latent cerebellar/brainstem dysfunction? [J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2022, 141: 147-159.

53. CHOI J H, KIM H, SHIN J H, et al. Eye movements and association with regional brain atrophy in clinical subtypes of progressive supranuclear palsy[J]. J Neurol, 2021, 268(3): 967-977.

54. PINKHARDT E H, JÜRGENS R, BECKER W, et al. Differential diagnostic value of eye movement recording in PSP-parkinsonism, Richardson’s syndrome, and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease[J]. J Neurol, 2008, 255(12): 1916-1925.

55. OTERO-MILLAN J, SERRA A, LEIGH R J, et al. Distinctive features of saccadic intrusions and microsaccades in progressive supranuclear palsy[J]. J Neurosci, 2011, 31(12): 4379-4387.

56. AVERBUCH-HELLER L, HELMCHEN C, HORN A K, et al. Slow vertical saccades in motor neuron disease: correlation of structure and function[J]. Ann Neurol, 1998, 44(4): 641-648.

57. POLETTI B, SOLCA F, CARELLI L, et al. Association of Clinically Evident Eye Movement Abnormalities With Motor and Cognitive Features in Patients With Motor Neuron Disorders[J]. Neurology, 2021, 97(18): e1835-e1846.

58. AUST E, GRAUPNER S T, GÜNTHER R, et al. Impairment of oculomotor functions in patients with early to advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[J]. J Neurol, 2024, 271(1): 325-339.

59. YOUN C E, LU C, CAUCHI J, et al. Oculomotor Dysfunction in Motor Neuron Disease[J]. J Neuromuscular Dis, 2023, 10(3): 405-410.

60. ARMSTRONG R A. Visual signs and symptoms of multiple system atrophy[J]. Clin Exp Optom, 2014, 97(6): 483-491.

61. ROTTACH K G, RILEY D E, DISCENNA A O, et al. Dynamic properties of horizontal and vertical eye movements in parkinsonian syndromes[J]. Ann Neurol, 1996, 39(3): 368-377.

【引用格式】李慧,赵玲,徐晓娅. 眼动追踪技术在神经退行性疾病认知功能障碍中的研究进展[J]. 中国神经精神疾病杂志,2024,50(10):608-614.

【Cite this article】LI H,ZHAO L,XU X Y.Research progress of eye tracking technology in cognitive impairment of neurodegenerative diseases[J]. Chin J Nervous Mental Dis,2024,50(10):608-614.

DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0152.2024.010.008